Teaching the Arts in a State Prison Classroom

Posted by Apr 09, 2019

Dr. Lauren Neefe

Kate McLeod

During this past school year, Dr. Lauren Neefe with Common Good Atlanta reached out to the High Museum to do a guest lecture experience at Metro Reentry Facility, a state prison reentry program in Atlanta. We came to one class during a series of art and art history lectures at the facility. This blog post features Dr. Neefe’s experience with incorporating art from the High Museum and music in her curriculum.

Rainer Maria Rilke famously lands his 1908 poem “Archaic Torso of Apollo” on the most radical of injunctions: “You must change your life.” Weighing in at a mere half line, the sentence punctuates a four-stanza body scan of the sculpture—denuded of head, arms, legs, and phallus—that gives the poem its title. American poet Mark Doty has called it “the sharpest last-minute turn in sonnet history.” The shock of it does have a way of raising the hair on the neck.

Last fall, as the volunteer site director for Common Good Atlanta’s education program at Metro Reentry Facility, the newly reopened and “re-missioned” state prison in southeast Atlanta, I was given the opportunity to give a series of lectures on art and art history to the 28 incarcerated students in our college course. My doctoral training is in English literature and poetry, not art history; but I knew I was up to the task of introducing art as a contested category of culture and knowledge, and I knew I wanted to begin with Rilke’s sonnet. Everything about the daily experience of an incarcerated person surely enforces the imperative of that final line as dictum rather than votive offering. If Rilke’s poetic gambit turns on the relay from speaker to reader of the ruined sculpture’s invitation, then my educational gambit was to relay the invitation in kind. Maybe I could reframe the obligations of punitive discipline as the pleasures of an aesthetic one. Maybe the students and I could write over the indignities of one kind of suffering with the dignity of another, the kind artists and scholars know as passion.

Full disclosure: I also wanted to sneak poetry in behind art and teach ekphrasis. Eyes on the prize, though, I used Lecture 1 to present Rilke’s poem as an argument—a rhetorical mode, Doty notes, that the sonnet’s contrapuntal structure takes to exceptionally well. As argument, the poem becomes one authoritative position among many in a field of debate about the definition of art. Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary presented a second, the Oxford English Dictionary a third. Apollo’s torso a fourth; Duchamp’s urinal a fifth.

My goal in Lecture 2 was to contextualize this field of debate with Janson’s introduction to the traditions of Western art and Raymond Williams’s historicized account of the changes wrought by the Industrial Revolution in five “key words”: industry, democracy, class, culture, and art. Extending the field into the present, we then watched the music video for the Carters’ (a.k.a. Beyoncé and Jay-Z) song “Apes**t.” A polemic about the institutional authority that determines which beauty qualifies as “art,” the video is staged in the Louvre, the very institution in which Rilke likely encountered his archaic torso. As Rodin’s secretary in 1905–6, the poet found himself touring Paris in order to learn how to look at things in the “new,” modernist way the sculptor did. Bringing the point home was self-taught artist André Henderson, who took the students through a selection of his recent paintings. From a series titled “Journey,” the dreamlike compositions envision the underwater theater of the Middle Passage. After he spoke, André gave the students an opportunity to draw an “intuitive” self-portrait, which some of them shared at the end of class.

Because these lectures on art were at the same time lessons in how to build an argument, I asked the students now to compose their own argument as homework. They had to write a 300-word paragraph that answered the following question, drawing on specific evidence from the video and readings: Why do Beyoncé and Jay-Z face the viewer together with the Mona Lisa at the beginning of the video, only to turn away from the viewer and toward the Mona Lisa at the end?

Voilà! a sampling of the range of their arguments:

- The reason the Carters look at the Mona Lisa in the end is to show what is considered to be art now.

- It is a switch from portraying themselves as art to being observers of art.

- At the end of the video, they face the artwork in contempt.

- When the Carters stand in front of the Mona Lisa and look out with her, they are openly challenging critics with the same mockery and sarcasm that radiates from the Mona Lisa.

- The Carters are like the man looking for admittance in [Kafka’s] “Before the Law” when they are looking out at us with the Mona Lisa.

- The Carters are standing in front of the Mona Lisa to make the statement that the beauty that once made people go “apeshit” for the Mona Lisa is over and they are the new beauty that makes people go “apeshit” for a successful black couple.

- When they turn to face the Mona Lisa, they are paying homage to a predecessor in creative process and leaps of imagination.

- By looking out with the Mona Lisa the Carters are letting the viewers know that they are more important than this piece of art. They face the Mona Lisa at the end to command the viewers, like Rilke does in “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” to “change your life.”

- When they turn to face the Mona Lisa, Beyoncé and Jay-Z see the Mona Lisa as art as well as the Mona Lisa sees Beyoncé and Jay-Z as art.

Not bloody bad. I opened Lecture 3 by reflecting this selection of thesis claims back at them as their authoritative contribution to the field of debate that was framed by all the definitions of art we had been reading and discussing. Joining us that day to guest-lecture was Meg Williams, Coordinator of School and Teacher Services at the High Museum of Art. She might have gone a little apes**t at their insights.

In any case, Meg took the floor to introduce Atlanta’s primary institutional authority on art. She focused in particular on the process by which one of its current exhibitions, “With Drawn Arms: Glenn Kaino & Tommie Smith,” came into being. Someone has to make the case to the High’s curators that this collaboration between a multimedia artist and an Olympic athlete is culturally significant and, for that matter, profitable. Who made that argument? To whom? How did they make it? And did the argument end there? Meg’s presentation was both turning back the veil on one institution’s power to define art and setting up the last homework assignment: Pitch a show to the High’s curators in 500 words.

Their ideas ranged from subjects mostly unrelated to the purview of Atlanta’s Louvre (PTSD, relationships between incarcerated men and their children) to the loosely related (album covers, history of African-American music) and the spot on and intriguing. In this last category I put the proposed exhibits on tattoo art and body painting, art by a person with autism, and displays of the “perfect body.” With the students’ permission, I shared the pitches with Meg and her colleague Kate McLeod, Head of School and Teacher Services at the High. There might have been a little more apes**t.

One student cheekily punned on the museum’s name with “Cannabis”:

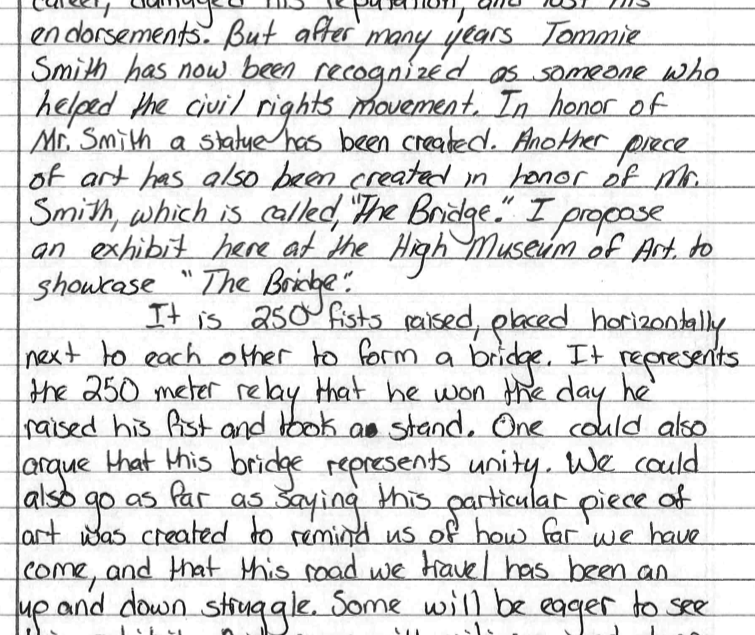

Another student, since released and now a returned citizen, retrofitted a pitch to the “With Drawn Arms” exhibition he learned about in class:

A resourceful group of students took inspiration from a de Young Museum postcard they had for the recent exhibition “Revelations: Art from the African American South.” Displaying a keen sense of audience and market, they recommended a similar exhibit for the High. Kate forwarded their proposal to the Boone Curator of Folk and Self-Taught Art, Katie Jentleson, who was so excited by their idea that she reached out to me by email:

They selected two wonderful works that were featured in that show, by Thornton Dial and Mary Lee Bendolph, and I was very moved by how they linked some of the experiences of these artists to contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter. I also loved their comment, “Art is not limited to rich white people. Anyone with a story can create art.” I could not have said it better myself! That is exactly what I think when I look at the work of self-taught artists, and is part of what inspires me so much about their work.

All of the incarcerated students at Metro have stories. Some of them indeed create art from those stories—occasionally from the one that sentenced them to the Georgia Department of Corrections, more often from the many others that shape the person who shows up in our classroom every Monday night. Some students have already trusted me with their creations. I have trusted some of them with mine.

Must we change our lives? Honestly, I don’t know. I am certainly changed by this work, call it art or god or—what we care about at Common Good—dignity. But I’m not much convinced by this poem that art asks of us any such thing. Rilke is tempted to feel like he is enjoined to radical action because, by the end of his lurid gazing, he realizes that the work of art knows him better than he knows himself. “For here,” the next-to-last line declares, “there is no place that does not see you.”

That’s the line that haunts me. Not surprisingly, it resonated with this particular group of students as well. Many of them referred to in their written assignments. It captures, I think, the argument that Rilke’s poem enacts in the shadow of its more flamboyant closing gesture. The poem, as the work of art it describes, teaches us how to look, what we might see, and how to begin to respond to the unknown unknowns when they at last become known to us. This slower-burning claim within the poem is borne out by the Metro students’ work over the course of three art lectures this fall and by my experience working with the Common Good students at Phillips State Prison the last three years. It is what Rodin sent Rilke out groping through the Louvre for in the first place.