The Mission of Theater: The Contract of Showtime

Posted by May 04, 2017

Jeffrey Pufahl, MFA, LMUS

I gathered everyone into a circle and said,

“Everyone raise your right hand and repeat after me: I promise to attend all forthcoming rehearsals and to bring my script with me every time. I promise to arrive on time, because when I’m late I let my company down because they made it here on time and are ready to work. I promise to work on my lines for at least one hour this week outside of rehearsal time because when I don’t know my lines my company members do not feel like I’m invested in this project.”

There are basic contracts theater makers enter with each other when they start a project. These unwritten rules govern the creation of a piece of theater. These credos are common knowledge among theater professionals, but are unknown to non-theater artists.

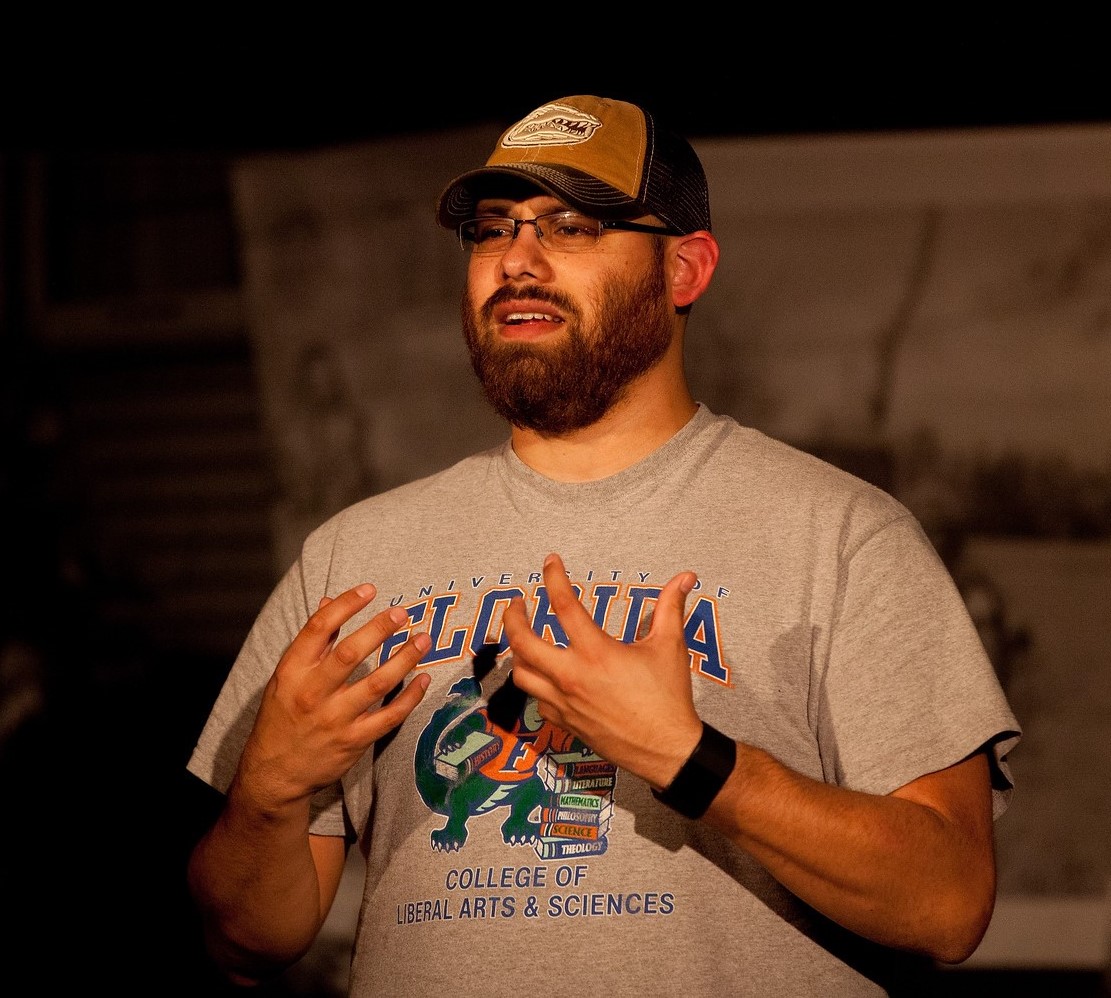

While directing a community theater project with four veterans and a military wife, I was struggling with how to bring the group together. Several participants were missing rehearsals and had not learned their lines, while others had been present at every rehearsal and had gone to great lengths to memorize their stories. As a director, I had to be understanding and generous with the company; they all had busy lives and personal issues to deal with, but at some point, if everyone didn’t make this play a priority, the show wasn’t going to come together.

The moment of truth came for our production about two thirds through the rehearsal process. We just hadn’t pulled it together, and I could sense the frustration mounting amongst the company. I was struggling with how to address the issues while not singling out company members, and also pondering what language to use—what would get the best response from the veterans? It felt like kindness and gentle urging just wasn’t doing the job. I consulted with Sergeant C. and he said, “I’m a Marine. I’m mission oriented; we need to do what it takes to get this job done.”

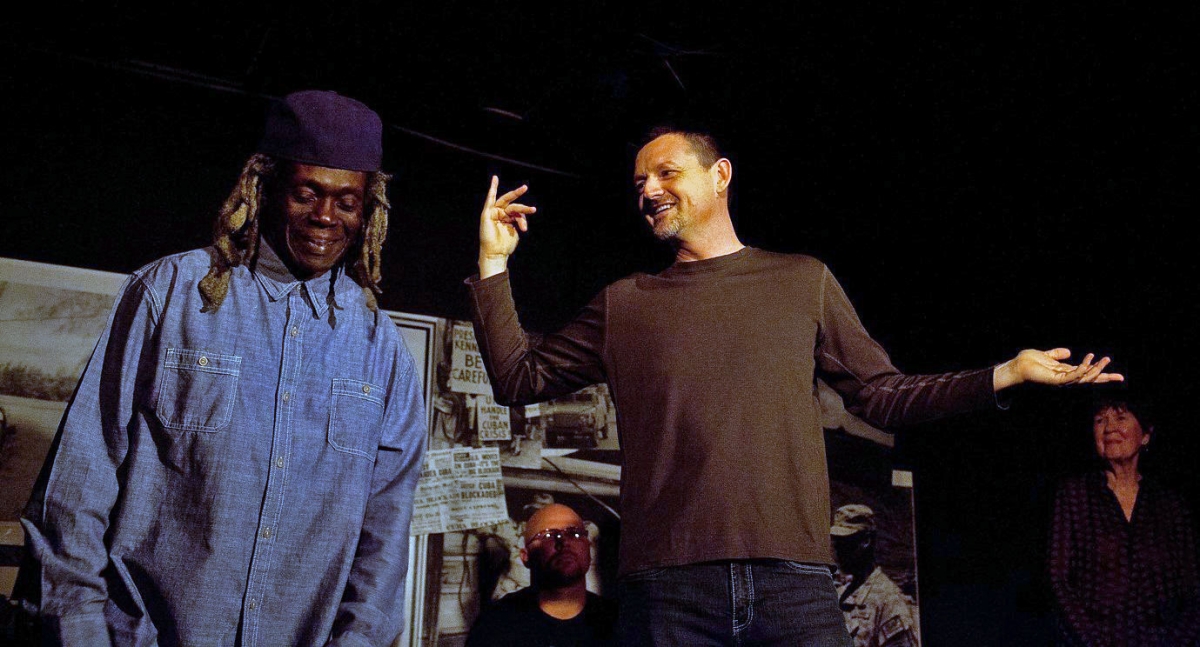

So we gathered in a circle, raised our right hands, and repeated the oath together. We were all smiling when we started, but as we spoke something began to shift. I could feel the power of the words begin to take hold as we made eye contact and our intentions became known. We all needed to say those words together—some of us needed to say the words to others, while some just needed to say the words out loud and come to terms with the contract that was being made.

There is a deep connection a company of soldiers forms going through training, and an even deeper connection develops when the soldiers experience combat together. A similar thing happens to a company going through the process of creating theater: it might not be life or death, but the potency is still palpable. It’s amplified even more when the play is composed from the life stories of the veterans themselves. The terrain is a bit different; it’s a rocky road of memory and emotion—old, painful wounds emerge, and tears get beaten back or flow. It’s a battleground of a different sort but the rules are the same: no man left behind.

The contract we made changed our company—from that moment onward, we were in it together and were going to get through it like soldiers. The shift was amazing to watch; the participants started working together on their own—offering their houses for rehearsals, working on publicity, and talking about their costumes over impromptu dinners. A family was forming, and I could see that new friendships were to become lasting ones.

As the audience mingled in the lobby of the theater on opening night and began looking at the photos of the veterans on the set, I went backstage for a pre-show chat. The company was sitting in a circle talking, telling stories, and trying not to let their nervousness show. I gathered them into a circle for a few theater warm-ups and gave them a pep talk about the most important theater contract of all: showtime.

I have never experienced combat, but I imagine showtime is similar in many ways—heightened, condensed, timeless, and powerful—except showtime ends in sustained applause and all your fellow actors return to the dressing room with you. With showtime, we understand that what is shared at a performance is only between those who are there, and although the performance disappears forever once the lights are dimmed, what was shared remains and is carried by the audience. For the veterans who tell their stories through theater, their burdens can become a little lighter, a little more bearable—and that can make the pain of telling worthwhile.

“Telling: Gainesville” ran for seven sold-out performances at the Actors’ Warehouse in Gainesville, FL over two weeks in November of 2016. The Telling Project is a national performing arts non-profit that employs theater to deepen our understanding of the military and veterans’ experience. Through performance, The Telling Project puts veterans and military family members in front of their communities to share their stories, sometimes for the first time ever. It’s a cathartic and healing process that increases with each performance, as the experience is accepted and heard, and a new sense of unified purpose is forged. “Telling: Gainesville” was made possible by a grant from the Florida Humanities Council. The Telling Project is a member of the National Initiative Directory, an online resource of the National Initiative for Arts & Health in the Military at Americans for the Arts.