Natasha Hoehn

Unleashing Creativity in the Classroom via Common Core Standards

Posted by Sep 13, 2012

Natasha Hoehn

When I think of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS), I think of Martha Graham. I think of John Keats.

When I think of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS), I think of Martha Graham. I think of John Keats.

My imagination runs wild with images of fun, inspired, powerful learning experiences for kids. There is no doubt in my mind that this transition opens the door for new energy and greater opportunity to elevate the joyful practice and rigorous study of the arts in our classrooms across the nation.

It says something powerful to me that the authors of the Math and English Language Arts (ELA) standards often begin their explanations of the CCSS through art. Last month, for example, I savored several lovely minutes gazing at a sketch of a Grecian vase in a hotel ballroom packed with K–12 district academic administrators. This wasn’t a time-filler. It was the keynote speaker himself, Phil Daro, describing the major transitions in the Math Standards by invoking Keats’ “Ode to a Grecian Urn.”

Keats’ image and accompanying poem, the pinnacle of art meeting craft, he explained, conveys the major instructional shifts of the new Math Standards. As as he spoke, I couldn’t help but think of the ways in which Keats’ ekphrastic approach, the poetic representation of a painting or sculpture in words, mirrors the function of math in human endeavors, as the beautifully-crafted ten-line stanzas, quatrain and sestet, the lines explore the relationship between art and humanity.

Keats’ topic and craft also invoke CCSS-Math’s call for increased focus, coherence, and rigor in conceptual understanding, procedural skill, and application, academic skills. Indeed, many of these academic math skills, as arts educators well know, can also be taught and reinforced well through music, visual arts, and dance. Rhythm as fractions. Choreography as geometry. Math as art.

Similarly, I’ve enjoyed experiencing David Coleman launch into his wonderfully compelling elucidations of the new English Language Arts standards by asking educators in the room read aloud a short first-person narrative, often from some of the world’s greatest artists. I’ve heard him guide a room full of the wonkiest of wonks through Martha Graham’s “This I Believe” testimony from NPR.

Read More

Mark Slavkin

Mark Slavkin

Yong Zhao

Yong Zhao

Niel DePont

Niel DePont

Susan Riley

Susan Riley

Amy Johnson

Amy Johnson

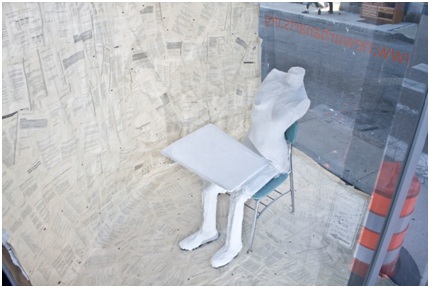

My classroom.

My classroom.

Maria Barbosa

Maria Barbosa

Paul King

Paul King

Sarah Zuckerman

Sarah Zuckerman

The Common Core standards in English Language Arts (ELA) and Mathematics are driving factors in the educational reforms facing public education today. As an arts educator in the schools, as a teaching artist who provides supplemental instruction with students in and out of school, as a cultural organization working to partner with a school, and/or as an arts education advocate, how can you approach the Common Core standards?

The Common Core standards in English Language Arts (ELA) and Mathematics are driving factors in the educational reforms facing public education today. As an arts educator in the schools, as a teaching artist who provides supplemental instruction with students in and out of school, as a cultural organization working to partner with a school, and/or as an arts education advocate, how can you approach the Common Core standards?

Kristen Engebretsen

Kristen Engebretsen

Rob Schultz

Rob Schultz

Dr. Joelle Lien

Dr. Joelle Lien